Tuesday, 29 July 2014

Map of Peterborough's War Dead

It has took me a month to compile the names of 587 names of the 628 Peterborough men and woman that died in the Great War. Please look at the map. Map of Peterborough's War Dead

You will have to click over the city of Peterborough to zoom in the map.

Sunday, 22 June 2014

When the 93rd went to war: Panoramic photograph offers a look at Confederation Square

Peterborough Examiner, 9 June 2014. By Elwood Jones

When the 93rd went to war: Panoramic photograph offers a look at Confederation Square

As he commented, "The coming on of the war, the rush of the first enlistments almost depleted the ranks owing to the number from the several companies that hurried to answer to the Call to Arms.

|

| 93rd Canadian Infantry Battalion Cap Badge. Credit: Militarybadgecollection.com |

There are two fascinating memoirs that relate to local men who enlisted very early. Gordon Hill Grahame, whose book Short Days Ago (Toronto, Macmillan, 1972) was canoeing to New York City with two friends from Lakefield College School when they learned that war had been declared. Grahame immediately wired Colonel Sam Hughes asking permission to enlist in the Canadian Army. Hughes told him to report for service in Port Hope and then get quickly to Camp Valcartier, near Québec City. Grahame ran into others struck with this inexplicable enthusiasm. People were unaware of the horrors of that war. On September 22, his battalion, the 2nd Battalion, was loaded on a transport, the S. S. Cassandra, which Grahame noted was moored next to the ruins of the Norwegian ship Storstad that had rammed the Empress of Ireland, causing about 1,000 deaths. (Ed: 1914 sinking, Largest Civilian Naval Disaster in Canadian Waters)

By October 3, the flotilla passed Gaspé. In a matter of six weeks all these volunteers were embarked for Europe. The other memoir, written by Thomas A. Morrow, was also written some forty or fifty years later, but is rich in detail. Both hard and digital copies of this memoir are in the Trent Valley Archives. He must have kept a diary. He noted that many of his schoolmasters had enlisted shortly after the declaration of war and he admired them as they marched along George Street to their training grounds. By Christmas the younger group, as he called them, were getting more excited and in January 1915 he was enlisting. He knew that he would have trouble meeting the size requirements, but a former teacher had taught him exercises to expand his lung capacity, and that proved enough for him to pass the medical.

At the time he had been working at Kent's drug store, at George and Hunter, and Kent said he was too small for the army. He enlisted and became part of the 39th Battalion, which included companies from Peterborough, Lindsay, Port Hope and Belleville and the four counties. By the end of March they were in Belleville where a former canning factory served as the barracks.

|

| 93rd Canadian Infantry Battalion "Peterborough", A Company. Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

Recently a panoramic photograph of the 93rd Battalion in May 1916, just before it headed to Europe, was donated to the Trent Valley Archives. This is a spectacular photograph, and copies of it are found in regional armouries, legions and museums. The photo stretched from Murray Street Baptist Church to the houses on the north side of McDonnel Street, and included the Armoury and the collegiate as well as buildings behind. The entire battalion was in the photograph, including four companies, the 93rd Battalion Band, and ancillary units such as the Signalers and the Machine Gun Section. In the background there was a Model T car, and there were horses in the unit.

The war had not ended as quickly as people had hoped in the summer of 1914, and the loss of life by Canadian soldiers was staggering. Reinforcements were needed, and recruitment drives were necessary. As part of processing this photograph for the archives we decided to do some research especially in the files of the Peterborough Examiner.

The taking of the photograph, on May 19, 1916, was of wide local interest. The goal was to have a complete photographic record of the battalion at this moment. Roy Studio had charge of the photo session but a 42-centimetre camera was brought to Peterborough by the Toronto Panoramic. This was the largest group photographed in Peterborough and the picture was perhaps the biggest taken in Peterborough. The Battalion was formed in a large semi-circle and the camera moved in the arc. Everyone had to remain still during the entire process. And there were no drills during the morning session. Roy Studio was selling copies of the photos within days.

|

| 93rd Canadian Infantry Battalion "Peterborough", B Coy Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

The 93rd grew out of events in the summer of 1915 when a big recruitment effort was made locally. In late August the government announced there would be a local training depot for 500 men and Peterborough would have an infantry headquarters. By early September the new regimental band, drawing members from the 57th band and from the Salvation Army. What became the 93rd was forming. Initially it was seen as part of the 80th Battalion based in Belleville, but hopes for a local battalion remained high. A Battalion with four companies: two local, and one from Cobourg and one from Lindsay was authorized. By October, it was announced that the new battalion would be the 93rd and those who had enlisted earlier, mainly for the 80th, were to form the nucleus of the new Battalion. By November it was decided that the new battalion would be confined to recruits from Peterborough County.

By Christmas 1915 the Battalion strength had reached 500. Men were recruited in Lakefield, Norwood, Apsley and Havelock as well as the city, and over the winter were allowed to train in those centres; this boosted recruitment. As well, the Examiner noted that about 350 men were recruited for other units, such as Mounted Rifles and Artillery.

According to the Examiner, between August 1914 and May 1916, 2,300 Peterborough men had joined the military. This was a ratio of one in nine of the local area compared to a national average of one in 25. Interestingly there were 35 pairs of brothers in the 93rd, and 15 instances of a father and a son joining.

Asa Huycke, whose Peterborough Music Company was located on George Street near Hunter, composed a "Marche Militaire" dedicated to the 93rd Battalion Band on the eve of the band going to Europe. On May 19, "Creatore's Famous Band" played Huycke's march at the Grand Opera House in Peterborough. There is a great reference to Giuseppe Creatore in the musical, "Music Man" in the tune, "76 Trombones."

The departure of the 93rd was delayed because of conditions at the Barriefield camp. Mayor J.J. Duffus presided over a farewell ceremony at Central Park (now Confederation Square since 1927) on May 29. A regimental fund that had been gathered by local citizens was given to the 93rd.

The following day, thousands lined the streets as the regiment marched to the Grand Trunk railway station. This was reported as the largest crowd that had ever gathered at the station. Several speakers complimented the units for "splendid behavior and efficiency" in developing a great fighting unit in a matter of months. The band of the 57th Regiment led the way with O Canada.The Examiner commented, "Special Train No. 1 was in waiting, and in a few minutes, without any confusion or trouble, the members of the band and of A and B companies were entrained." The crowd lined the road from Charlotte to King, oblivious to the mud which was "ankle deep." There were many tears as the train left at 9:30 a.m.

------------

Written by:

Elwood H. Jones, archivist of the Trent Valley Archives.

Great Article.

Labels:

57th Regiment,

93rd Battalion,

Confederation Square,

Ellwood Jones,

Peterboro,

Peterborough,

Peterborough Examiner,

Trent Valley Archives

Monday, 28 October 2013

Globe and Mail: 27 October 1914

Buried on page 8 of the Globe and Mail on 28 October 1914 is a tidbit of info of an special farewell event for Norwood soldiers. They would be heading to Kingston, Ontario for basic training. By May 1915, they would be in England, and by September 1915 they would be in the Trenches of France.

Here is the extract:

"WARM CLOTHING FOR BOYS

Norwood, Oct 27 - Ten young men who are leaving for the front were bidden farewell at the Town Hall last night. Stirring addresses were given by several prominent citizens. Each of the boys was presented a box of warm clothing by the Home Guard, Gun Club, and Lacrosse team, also comforters and wrist-lets by the Daughters of the Empire."

Here is the extract:

"WARM CLOTHING FOR BOYS

Norwood, Oct 27 - Ten young men who are leaving for the front were bidden farewell at the Town Hall last night. Stirring addresses were given by several prominent citizens. Each of the boys was presented a box of warm clothing by the Home Guard, Gun Club, and Lacrosse team, also comforters and wrist-lets by the Daughters of the Empire."

Thursday, 24 January 2013

Assault with the Bayonet in the Great War

Recently at Peterborough's Museum and Archives, students from Sir Sandford Fleming Community College Museum Management program showcased micro-exhibits. An excellent First World War bayonet exhibit was created.

To honour this student's work and future as a curator, I've created a link to Paul Hodge's article,

‘They don’t like it up ’em!’: Bayonet fetishization in the British Army during the First World War.

This entry focuses almost entirely on the use of bayonet's in combat in the First World War.

To honour this student's work and future as a curator, I've created a link to Paul Hodge's article,

‘They don’t like it up ’em!’: Bayonet fetishization in the British Army during the First World War.

This entry focuses almost entirely on the use of bayonet's in combat in the First World War.

Labels:

19th Battalion,

20th Battalion,

British Bayonet,

Canadian National Exhibition,

Great War,

Lee Enfeld,

Peterboro,

Peterborough World War I,

Toronto Armouries

Sunday, 6 January 2013

Stunning Photo: German Soldiers during the Kaiserschlacht, May 1918

Click to Enlarge Photograph

German Post Card, 1918

Labels:

British Soldiers,

Chemin des Dames,

German Soldier,

Kaiserschlacht,

May 1918,

Non-Peterborough

Friday, 4 January 2013

First Nations Participation in Great War - Hiawatha's George Paudash

|

| Depiction of Aboriginal, Canadian Patriotic Fund Poster, 1916 Credit: web.vui.ca/davies |

|

| First Contingent Sailing from Canada, Oct 1914 Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

By October 1914 the fleet that was carrying the first of the Canadian Expeditionary Force reached Plymouth Hoe, England. Residents from the English towns and villages that surround the port city of Plymouth came out to the harbour to greet the soldiers from the distant cold colony that had come to the aid in the fight against ‘Prussian Barbarism.’

Civilians were surprised at what greeted them.

According to one Canadian officer, R.F. Haig of Fort Garry Horse Regiment, English residents were disappointed that the Canadians were not wearing feathers and

pelts, or wearing traditional headdresses. English citizens expected the Canadians of popular

literature. A country with a untamed

wild frontier, filled with proud native warriors wearing war-paint mounted on

horse back, living alongside hardworking farmers. Imagery of Canada

and the ‘noble savage’ aside; the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) sent

thousands of Aboriginal soldiers overseas during the First World War.

Aboriginal men had every reason not to want to fight for

Canada. In the decades leading up to 1914, officials acting on behalf of

the Crown and the Government enacted numerous laws and policies that oppressed Aboriginal

people. Similar to the Indigenous population of Australia, contact with

Europeans brought misery and hardship upon the native population. The once

proud warrior nations that hunted buffalo in the Great Plains or traversed the Great

Lakes of Ontario were brought to the brink of extinction by disease, war, and

euro-centric policies that placed First Nations people into a system of

reserves often located on unsuitable destitute land. European colonizers attempted

to take all native children away from their families and place them into

residential schools, where the children would be beaten, and in some cases

sexually assaulted by predatory clergymen; all in an effort to have the ‘Indian’

taken out of them.

|

| Minister Sam Hughes Touring Arras, 1916. Credit: IWM |

Despite the systematic oppression and societal exclusion,

many Aboriginal men made the decision to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary

Force. As wards of the crown, natives

were not granted the rights of citizenship, and therefore were legally excluded

from fighting overseas. The Minister of the Militia, Sam Hughes, a xenophobic

Orangemen, tried to further discourage the recruitment of natives by stating:

“While British troops would be proud to be associated with their fellow

subjects, yet Germans might refuse to extend to them the privileges of

civilized warfare.” Many local battalion officers overlooked the Minister’s

concerns and allowed Aboriginals to enlist.

|

| Map of First Nations, Central Ontario Credit: Ontario Aboriginal Affairs |

“The fighting spirit of my tribe was not quelched through reservation life. When duty called, we were there and when we were called forth to fight for the cause of civilization, our people showed all the bravery of our warriors of old.”

In Central Ontario there is several First Nations that near

Peterborough and the Kawarthas, Northumberland, and Quinte Region. Aboriginal

men from: Alderville, Curve Lake, Hiawatha, Chippewas of Rama and Georgina

Island, and Mississauga of Scuggog, and the Tyendinaga Mohawks were all eligible

to enlist in Peterborough in the No. 3 Military District.

George Paudash

George Paudash

|

| George Paudash, Nov. 1914. Credit: http://21stbattalion.ca |

In the November 1914, two brothers from the Hiawatha reserve

located outside of Peterborough enlisted in the 21st Battalion

(Eastern Ontario). George Paudash, age 24; and

Johnson Paudash, age 39; were trained and quickly sent overseas. The brothers

arrived in France in the Autumn 1915, and spent several months in the M and N

trenches south of Ypres in Belgium. The men of the 21st Battalion learned to snipe, scout, and exist under shell fire at the M and N trenches.

Months later the first rotations in the lines, the 21st Battalion would be pushed into their first actual pitched fight with the enemy, at the St. Eloi Craters. After the battle of the craters, the

youngest brother, Corporal George Paudash, developed numerous abdominal pains

and was sent to hospitals in England before returning home.

George’s older brother, Johnson Paudash, would find fame as one of

Canada’s greatest snipers.

(Next Entry)

(Next Entry)

Labels:

21st battalion,

Aboriginal,

First Nations,

Hiawatha,

Indian,

M and N trenches,

Native,

Sniper,

St. Eloi

Thursday, 15 November 2012

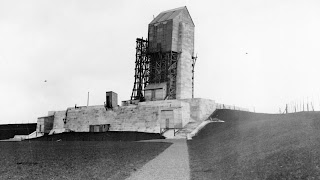

Canadian Vimy Ridge Memorial

|

| The Shell scared landscape of Vimy Ridge -90 years later Credit: Burkepaterson.com |

|

| Canadian National Vimy Ridge Memorial |

|

| Notre Dame de Lorrette - France's largest Cemetery |

This entry will showcase the Vimy Monument; created by Walter Seymour Allward. Designer and Architect Allward was a renowned Canadian artist. Allward created monuments for the War of 1812, Boer War (South African War), Bell Telephone, Stratford War Memorial (1922), Brantford War Memorial (1933), and the Peterborough Citizens' Memorial (1929).

.jpg) |

| Mother Canada Mourning her lost sons. Credit: BurkePaterson.com |

Allward was a busy artist, while he was busy designing the Brantford and Peterborough Memorial, Walter Seymour Allward was also busy working on his latest commission from the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission in 1925 - Vimy Ridge. Allward and his labourers spent 11 years constructing Canada's largest Great War monument, on ground that many Canadians consider sacred. In the next few years Canadians will become very familiar with Allward and Vimy Ridge; Allward's work is now on the $20 tender.

|

| Walter Allward posing infront of his incomplete Vimy Ridge Monument Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Aerial view of Vimy Ridge dedication, 1936. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleaf.ca |

|

| Early 1930s - Laying foundation. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Inscribing names of 11,000 Canadian soldiers that died in France with no known grave. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Progress on the monument. Credit: Library and Archives Canada & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Early 1930s - In 1922 France donated 245 acres, centred on Hill 145 to Canada. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Laying the base of the 24 foot tall monument base. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

Labels:

1936,

20 Dollar,

Allward,

Canadian National Vimy Ridge Memorial,

Cenotaph,

Peterborough,

Vimy,

Vimy Memorial,

Vimy Monument,

Vimy Ridge,

Walter Seymour Allward

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)