|

| Credit: Major Bennett Bus, Flickr.com, VB5215 |

The white and green buses operated by Peterborough Transit

are on nearly every major arterial road in the city. The Major Bennett #12 bus

is a familiar sight on Aylmer Street and near the newly renovated Lansdowne

Place Mall. The commuters that use the Major Bennett route likely haven’t

considered the origin of the name. Major Bennett Drive was named after

Peterborough’s first casualty of the First World War, Major George Bennett.

|

| Photograph of Major G.W. Bennett, Credit: Peterborough Examiner, 1915 |

George Bennett was a prominent resident of the small city of

18,000 people. He was born in 1864 in North Monaghan Township and worked a

civil servant for the Government of Ontario. He rose to the prestigious rank of

Superintendent of the Department of Public Works overseeing provincial roads in Northern Ontario. The tall dark

haired 49 year old bachelor had served with the local Peterborough militia for

over 25 years. After many nights at the Peterborough Armouries on George

Street, Bennett received his officer’s commission with the 57th "Peterborough

Rangers" Regiment.

|

| Picture of troops in Ypres in June 1915 with bayonets. Note how the Belgian countryside still had trees - not yet mud and siege warfare. Credit: Wikipedia Commons |

When Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914, 115 soldiers

from Peterborough’s 57th Regiment rushed to volunteer for overseas

service. The eager Peterborough volunteers that were selected for service were

to be led by Peterborough’s own Major Bennett. The first batch of Peterborough

recruits were assigned to the 1 Company, 2nd Battalion (Eastern

Ontario) in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. After months of training in

Quebec, and in England, they took their place in the front line against the

Germans.

|

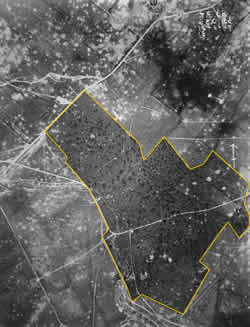

| Route of 2nd Battalion on 22 April 1915 Credit: The History of the 2nd Canadian Battalion (Eastern Ontario Regiment), C.E.F., 1947 |

At 7pm on 22 April 1915, the Bennett’s battalion witnessed

the first use of chlorine gas in warfare. Click here to read about the attack. Bennett and his men were stationed in reserve in rest billets

(huts) in the town of Vlameringhe, Belgium. Witnesses from the 2nd

Battalion recall watching French troops stagger past the Canadian lines in full

retreat; some soldiers “dropping into ditches in convulsions of vomiting.” By

8:30pm, the commander of 3rd Brigade, war hero and holder of the

Victoria Cross, Richard Turner was in a complete panic. He ordered immediate

assistance to help launch an attack that would get the Germans out of

Kitcheners’ Wood. It would take several hours of marching on Belgian roads,

stopping intermittently to let ambulances with wounded soldiers pass, before the

2nd Battalion arrived at the designated rendezvous point.

|

| Photograph of the remains of Kitcheners' Wood, taken in 1918. Credit: Great War Forum |

|

| Photograph of Kitcheners' Wood, June 1917. Credit: Greatwar.co.uk |

At roughly 10 pm, the first two Canadian units attempted to

retake Kitcheners’ Wood. Attacking from southerly direction, the 16th

Battalion and 10th Battalions made a 200 yard running charge over

open ground, facing fire from the chattering German machine guns as they

entered into the woods. Within minutes the attack had stalled, the commander of

the 10th Battalion lay bleeding to death after receiving 5 bullets to the groin. His men were now engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with Germans in

the east, west and in the interior of the wooded area. By the time roll call

came next morning, the 16th Battalion only had 193 men out of 813.

The 10th Battalion’s casualties were much worse, in a report made

three days after the battle; an officer wrote that the unit only has “a small

party of men” left.

|

| Location of Kitcheners' Wood and Canadian Monument. Credit: Google Maps |

As Major Bennett and his men felt their way forward in the

dark, they could see and hear the muzzle flashes and sound of gun fire on their

left flank. They knew that their comrades in No. 3 Company needed assistance.

After reaching cover of a hill, Bennett ordered a scout to report on the

developing situation. After examining the terrain and referencing his position

on a map, Major Bennett crawled back to his men. The battalion’s commander, Lt.

Col. Watson, approached Bennett’s lagging troops. Watson bellowed to his subordinate that an attack

must be carried out before morning. Major Bennett lay on his stomach on the

side of a hill with his men awaiting orders, he may have thought of the irony

of being in a farm field similar to his own, only thousands of miles away from North

Monaghan. Bennett was told to attack, and as a good soldier he would follow

that order.

As dawn began to break the night sky over Langemarck, Major Bennett prepared to meet his destiny. Bennett put his whistle to his lips, grabbed his service revolver out of the holster, and ordered his men to fix bayonets. After the 15 inch steel blades snapped onto the rifles, the Major stood up and ordered the men to get up. He inhaled. Waving his arm forward he blew his whistle and charged over the hill.

As dawn began to break the night sky over Langemarck, Major Bennett prepared to meet his destiny. Bennett put his whistle to his lips, grabbed his service revolver out of the holster, and ordered his men to fix bayonets. After the 15 inch steel blades snapped onto the rifles, the Major stood up and ordered the men to get up. He inhaled. Waving his arm forward he blew his whistle and charged over the hill.

The German troops in Kitcheners’ Wood saw the soldiers from

Peterborough as they descended down the sloping hill. Within seconds, the

Germans unleashed a storm of bullets against the Canadians as they ran directly

at the German line. As a leader of infantry charge, Major Bennett was one of

the first men to be hit. Survivors of the failed attack on Kitcheners’ Wood

wrote back to family in Peterborough that Major Bennett was killed instantly

when he was hit in the head and stomach with a burst of machine gun fire. Private

James Bills of Sherbrooke Street, who was wounded in the charge, wrote back home:

“The Canadians did grandly the past few weeks, but our company lost every

officer in one day. . . He [Bennett] was loved by all men in the company, and,

believe me, they would follow him anywhere.”

The 2nd Battalion attack on Kitcheners’ Wood

failed. Almost all of the soldiers No. 1 Company were killed or wounded in the

charge. After two days of fighting, the

battalion had 494 soldiers at roll call; 540 of the 1,034 men in the unit had

died, been wounded or captured. On April 25th 1914, the first news

of the battle arrived in Peterborough. Initially, the news reported that the

Canadians had succeeded; eventually word came to prepare for large numbers of causalities.

On April 28th came the news of Bennett’s death. Letters of condolence

poured in from the premier, Prime Minister, and city councillors. In early May

a large Anglican memorial service was held in Bennett’s honour. The service included

a solemn prayer for all the families in Peterborough that were in mourning or

waiting to hear information of their relatives in Ypres. His death represented

the war coming to Peterborough. For residents of the city, the Great War

was no longer a European side show that they read about in the paper.