Showing posts with label Peterborough. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Peterborough. Show all posts

Tuesday, 29 July 2014

Map of Peterborough's War Dead

It has took me a month to compile the names of 587 names of the 628 Peterborough men and woman that died in the Great War. Please look at the map. Map of Peterborough's War Dead

You will have to click over the city of Peterborough to zoom in the map.

Sunday, 22 June 2014

When the 93rd went to war: Panoramic photograph offers a look at Confederation Square

Peterborough Examiner, 9 June 2014. By Elwood Jones

When the 93rd went to war: Panoramic photograph offers a look at Confederation Square

As he commented, "The coming on of the war, the rush of the first enlistments almost depleted the ranks owing to the number from the several companies that hurried to answer to the Call to Arms.

|

| 93rd Canadian Infantry Battalion Cap Badge. Credit: Militarybadgecollection.com |

There are two fascinating memoirs that relate to local men who enlisted very early. Gordon Hill Grahame, whose book Short Days Ago (Toronto, Macmillan, 1972) was canoeing to New York City with two friends from Lakefield College School when they learned that war had been declared. Grahame immediately wired Colonel Sam Hughes asking permission to enlist in the Canadian Army. Hughes told him to report for service in Port Hope and then get quickly to Camp Valcartier, near Québec City. Grahame ran into others struck with this inexplicable enthusiasm. People were unaware of the horrors of that war. On September 22, his battalion, the 2nd Battalion, was loaded on a transport, the S. S. Cassandra, which Grahame noted was moored next to the ruins of the Norwegian ship Storstad that had rammed the Empress of Ireland, causing about 1,000 deaths. (Ed: 1914 sinking, Largest Civilian Naval Disaster in Canadian Waters)

By October 3, the flotilla passed Gaspé. In a matter of six weeks all these volunteers were embarked for Europe. The other memoir, written by Thomas A. Morrow, was also written some forty or fifty years later, but is rich in detail. Both hard and digital copies of this memoir are in the Trent Valley Archives. He must have kept a diary. He noted that many of his schoolmasters had enlisted shortly after the declaration of war and he admired them as they marched along George Street to their training grounds. By Christmas the younger group, as he called them, were getting more excited and in January 1915 he was enlisting. He knew that he would have trouble meeting the size requirements, but a former teacher had taught him exercises to expand his lung capacity, and that proved enough for him to pass the medical.

At the time he had been working at Kent's drug store, at George and Hunter, and Kent said he was too small for the army. He enlisted and became part of the 39th Battalion, which included companies from Peterborough, Lindsay, Port Hope and Belleville and the four counties. By the end of March they were in Belleville where a former canning factory served as the barracks.

|

| 93rd Canadian Infantry Battalion "Peterborough", A Company. Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

Recently a panoramic photograph of the 93rd Battalion in May 1916, just before it headed to Europe, was donated to the Trent Valley Archives. This is a spectacular photograph, and copies of it are found in regional armouries, legions and museums. The photo stretched from Murray Street Baptist Church to the houses on the north side of McDonnel Street, and included the Armoury and the collegiate as well as buildings behind. The entire battalion was in the photograph, including four companies, the 93rd Battalion Band, and ancillary units such as the Signalers and the Machine Gun Section. In the background there was a Model T car, and there were horses in the unit.

The war had not ended as quickly as people had hoped in the summer of 1914, and the loss of life by Canadian soldiers was staggering. Reinforcements were needed, and recruitment drives were necessary. As part of processing this photograph for the archives we decided to do some research especially in the files of the Peterborough Examiner.

The taking of the photograph, on May 19, 1916, was of wide local interest. The goal was to have a complete photographic record of the battalion at this moment. Roy Studio had charge of the photo session but a 42-centimetre camera was brought to Peterborough by the Toronto Panoramic. This was the largest group photographed in Peterborough and the picture was perhaps the biggest taken in Peterborough. The Battalion was formed in a large semi-circle and the camera moved in the arc. Everyone had to remain still during the entire process. And there were no drills during the morning session. Roy Studio was selling copies of the photos within days.

|

| 93rd Canadian Infantry Battalion "Peterborough", B Coy Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

The 93rd grew out of events in the summer of 1915 when a big recruitment effort was made locally. In late August the government announced there would be a local training depot for 500 men and Peterborough would have an infantry headquarters. By early September the new regimental band, drawing members from the 57th band and from the Salvation Army. What became the 93rd was forming. Initially it was seen as part of the 80th Battalion based in Belleville, but hopes for a local battalion remained high. A Battalion with four companies: two local, and one from Cobourg and one from Lindsay was authorized. By October, it was announced that the new battalion would be the 93rd and those who had enlisted earlier, mainly for the 80th, were to form the nucleus of the new Battalion. By November it was decided that the new battalion would be confined to recruits from Peterborough County.

By Christmas 1915 the Battalion strength had reached 500. Men were recruited in Lakefield, Norwood, Apsley and Havelock as well as the city, and over the winter were allowed to train in those centres; this boosted recruitment. As well, the Examiner noted that about 350 men were recruited for other units, such as Mounted Rifles and Artillery.

According to the Examiner, between August 1914 and May 1916, 2,300 Peterborough men had joined the military. This was a ratio of one in nine of the local area compared to a national average of one in 25. Interestingly there were 35 pairs of brothers in the 93rd, and 15 instances of a father and a son joining.

Asa Huycke, whose Peterborough Music Company was located on George Street near Hunter, composed a "Marche Militaire" dedicated to the 93rd Battalion Band on the eve of the band going to Europe. On May 19, "Creatore's Famous Band" played Huycke's march at the Grand Opera House in Peterborough. There is a great reference to Giuseppe Creatore in the musical, "Music Man" in the tune, "76 Trombones."

The departure of the 93rd was delayed because of conditions at the Barriefield camp. Mayor J.J. Duffus presided over a farewell ceremony at Central Park (now Confederation Square since 1927) on May 29. A regimental fund that had been gathered by local citizens was given to the 93rd.

The following day, thousands lined the streets as the regiment marched to the Grand Trunk railway station. This was reported as the largest crowd that had ever gathered at the station. Several speakers complimented the units for "splendid behavior and efficiency" in developing a great fighting unit in a matter of months. The band of the 57th Regiment led the way with O Canada.The Examiner commented, "Special Train No. 1 was in waiting, and in a few minutes, without any confusion or trouble, the members of the band and of A and B companies were entrained." The crowd lined the road from Charlotte to King, oblivious to the mud which was "ankle deep." There were many tears as the train left at 9:30 a.m.

------------

Written by:

Elwood H. Jones, archivist of the Trent Valley Archives.

Great Article.

Labels:

57th Regiment,

93rd Battalion,

Confederation Square,

Ellwood Jones,

Peterboro,

Peterborough,

Peterborough Examiner,

Trent Valley Archives

Thursday, 15 November 2012

Canadian Vimy Ridge Memorial

|

| The Shell scared landscape of Vimy Ridge -90 years later Credit: Burkepaterson.com |

|

| Canadian National Vimy Ridge Memorial |

|

| Notre Dame de Lorrette - France's largest Cemetery |

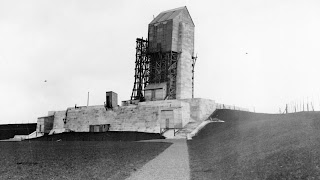

This entry will showcase the Vimy Monument; created by Walter Seymour Allward. Designer and Architect Allward was a renowned Canadian artist. Allward created monuments for the War of 1812, Boer War (South African War), Bell Telephone, Stratford War Memorial (1922), Brantford War Memorial (1933), and the Peterborough Citizens' Memorial (1929).

.jpg) |

| Mother Canada Mourning her lost sons. Credit: BurkePaterson.com |

Allward was a busy artist, while he was busy designing the Brantford and Peterborough Memorial, Walter Seymour Allward was also busy working on his latest commission from the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission in 1925 - Vimy Ridge. Allward and his labourers spent 11 years constructing Canada's largest Great War monument, on ground that many Canadians consider sacred. In the next few years Canadians will become very familiar with Allward and Vimy Ridge; Allward's work is now on the $20 tender.

|

| Walter Allward posing infront of his incomplete Vimy Ridge Monument Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Aerial view of Vimy Ridge dedication, 1936. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleaf.ca |

|

| Early 1930s - Laying foundation. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Inscribing names of 11,000 Canadian soldiers that died in France with no known grave. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Progress on the monument. Credit: Library and Archives Canada & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Early 1930s - In 1922 France donated 245 acres, centred on Hill 145 to Canada. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

|

| Laying the base of the 24 foot tall monument base. Credit: Library and Archives & mapleleafup.ca |

Labels:

1936,

20 Dollar,

Allward,

Canadian National Vimy Ridge Memorial,

Cenotaph,

Peterborough,

Vimy,

Vimy Memorial,

Vimy Monument,

Vimy Ridge,

Walter Seymour Allward

Monday, 5 November 2012

Peterborough’s Youngest Lost Soldier: Anthony Skarrizi

|

| Tyne Cot Commonwealth Cemetery Credit: Royal British Legion |

The expression “old men declare war, but the youth who

must fight and die,” comes to mind when visiting any Commonwealth War Graves

Commission Cemetery. Rows of white tombstones

mark the last resting place for a generation of young men of the British

Empire. Studies of death records have found that the majority of soldiers died

in their 20s, with the median age being 22-26 years old. Most of the soldiers were

cut down in the prime of their lives, leaving young wives and children to cope

with the loss of a missing partner and father.

|

| 14 year old and 8 month old Anthony Skarrizi Credit: http://21stbattalion.ca |

Researchers have come across the graves of soldiers from the

Great War that were too young to marry, or even shave. Recently

I have come across the story of Peterborough’s youngest fatality of the Great

War, Anthony ‘Tony’ Skarrizi who died during the last days of the Battle of

Passchendaele. Private Anthony Skarrizi was 16 years and 11 months old when he

died on 3 November 1917 outside of Passchendaele, Belgium.

Government Records show that Anthony Skarrizi was born in

Italy in November 1900. Like many Italian immigrants at the turn of the last

century, the Skarrizi’s moved to Canada in 1907 hoping of finding employment as

labourers. The young Anthony Skarrizi decided to join the military in August 1915.

Private Skarrizi falsely attested his birth year as 1897, making the adolescent

appear to be 18 to the Recruiting Sargent at the Peterborough Armouries, in all likelihood he was only 14 years and 8 months old.

|

| Canadian Military Police Corps (Provost) |

Private Skarrizi completed his military training in Canada,

and embarked for overseas service. After sailing to Liverpool, England he was

found to be underage and redeployed for permanent base duty. Military law

states all soldiers must be 18 to enlist in the military and 19 years old for

overseas service. Once his age was discovered, Skarrizi spent 6 months on base

duty being assigned to several guard and provisional units; he became an unruly

and irresponsible soldier. His young age combined long rotations in the much

hated “bullrings” (reinforcement camps) likely contributed to his declining

morale. By the winter of 1916-1917,

Private Skarrizi had several run-ins with the Canadian Provost Corps.

|

| Great War Military Depiction of Field Punishment No 1 |

He was arrested and court martialed four times for:

neglecting to obey an NCO, absent without leave on two occasions, and absent

from parade. The young soldier was punished by being restrained, having his pay

docked, and after his second conviction for being absent without leave, he was

given the dreaded Field Post No 1. According to the Manual of military law, the

Field Post No 1 punishment consists of restraining an individual at the feet and

hands and attaching the convicted soldier to a wagonwheel, or fencepost in a

public area, whereby all other soldiers could witness the punishment.

Two months after the last conviction, Skarrizi was

transferred to France with the 21st Battalion. One month after

landing in Boulogne, France, the young private was attached to Kingston’s 21st

(Eastern Ontario) Battalion billets in Villers Au Bois. The question arises: why and how would a

known underage soldier allowed to be sent overseas? No one knows. It is likely

that Officers decided to send Skarrizi to France because serving at the front would stop the adolescent Italian-Canadian

soldier from running away from the Canadian military camps.

|

| Terrain of Passchendaele Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

Unfortunately for Private Skarrizi, he joined the 21st

Battalion only several weeks before the Canadian Corps moved into Belgium to

take part in the Battle of Passchendaele. The four month long British led Passchendaele

offensive had almost ground to a halt. The British High Command jointly

employed their “shock troops” of Australian and Canadians to help

resolve the political and military mess that the British Generals had created

in attempting to take Passchendaele. The Canadian Commander, Arthur Currie, planned

to win the battle but slowly and in several phases in order to insure that the

Canadians did not suffer needless losses of men. This article will not go into the general history of the Passchendaele campaign. It is interesting to note that during the research for this entry, I found there was a lack of contemporary historical analysis into the Canadian involvement at Passchendaele.

|

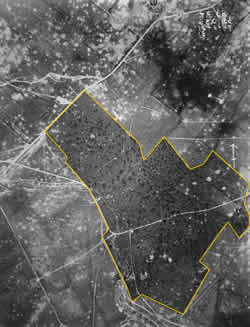

| Aerial Photograph of Passchendaele, displaying location of Crest Farm |

On the night of 3 November 1917 the 4th Canadian

Brigade relieved the Canadians that captured the lunar swampy landscape that

was Crest Farm at 2:45 AM. The relatively fresh 21st Battalion was

sent in to guard the recently captured Crest Farm by the 4th

Division. On the right was the 19th Battalion, and on the left the

21st Battalion was on left of Crest farm.

|

| 1917 Map and Location of Crest Farm Credit: McMaster Archives |

|

| Contemporary Photo of location of Crest Farm Credit: Google Maps |

|

| Menin Gate, Leper Belgium |

__________________________________________

Author would like to acknowledge the assistance and great research work provided by the 21st Battalion Website. Please visit them at http://www.21stbattalion.ca

Labels:

19th Battalion,

21st battalion,

4th infantry Brigade,

80th Battalion,

Crest Farm,

Italian-Canadian,

Passchendaele,

Peterborough,

Third Battles of Ypres,

Young Soldier,

Young Soldier Battalion

Monday, 29 October 2012

Peterborough's Confederation Square: Winter 1914 - 1915.

Here is an image of B Squadron, of the 8th Canadian Mounted Rifles.

The picture is taken on the North-east corner of Confederation Square - facing the George United Church (then a Wesleyan Church)

14 years after this photograph was taken, Peterborough's cenotaph would be unveiled at this very location. On 29 June 1929 by the Commander of the disbanded Canadian Corps, Sir General Arthur Currie, helped unveil the cenotaph. The monument to Peterborough's dead was designed by Walter S. Allward. After completing the Peterborough memorial, Allward sailed to France for his next project. Canada's national war monument - the stunning Vimy monument.

Labels:

21st battalion,

33rd Battalion,

36th Battalion,

8th CMR,

B Squadron,

Canadian Corps,

Confederation Square,

General Currie,

Peterborough

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

Peterborough Armouries and Peterborough Collegiate and Vocational School - Then and Now

Two photographs of the Peterborough Armouries and Peterborough Collegiate and Vocational School

1919 - 2009.

|

| Credit: Google Maps (2009) and Library and Archives Canada (1919) |

The Armouries building (on the left) was the base for the pre-war 57th Peterborough Rangers militia unit and during the First World War it was the home for the 93rd (Peterboro) Infantry Battalion. The Armoury also acted as recruiting depot for enlisting soldiers the Peteroborough area during the Great War and the Second World War. The Armoury is the current home to the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment.

The Peterborough Armoury was constructed between 1907 - 1909 during a period of great expansion and improvement to the Canadian Army. The Government of the time, led by Wilfrid Laurier, allocated more funding for the Department of Militia and Defense after the Boer War (South African War). Contracts were signed for new rifles, uniforms, and numerous armouries were built. During this period Canada also created its own Navy (1910). Laurier's cabinet Minister for Militia and Defense, Frederick W. Borden (cousin to future war-time PM Robert Borden), was in Peterborough for the opening of the architecturally stunning drill hall.

The building on the right is Peterborough Collegiate and Vocational School. It was constructed at the same time as the Armouries in 1908. The two building share some similarities in both structure, height, and colour. Local Peterborough historian and professor, Ellwood Jones, has noted that the location of the armoury, school, and nearby churches show that the city-planners wanted to centralize the Peterborough civic power one location. During the First World War, the headmaster of PCVS, Principal Kenner, complained in the local newspaper, regarding the regularity of fire drills at the armoury; and is quoted to have said at one City Council meeting that many "young pupils are too keen on soldiering rather than studies." Principal Kenner's assessment of the level of distraction found around the PCVS and the Armoury during 1915 - 1916 seems accurate. It is not hard to imagine young pupils stuck in class, periodically gazing out to the recruits drilling on Confederation Square. During this awkward arrangement between academics and warriors, the children had to learn over the noise of rifle practice, band practice, and the bellowing of orders from the cantankerous Regimental Sargent Major.

The photos were taken 90 years apart. The 1919 photograph was shot from an WWI era RFC airplane (from Camp Borden) during the early years of aerial photography (wing is visible in the left of the picture). The 1919 photo contrasts the 90 years of growth in Peterborough. A few hundred yards behind Murray and McDonnel Street, you can see farm fields. In 2009, all those family farms are gone, replaced by asphalt streets and homes.

Labels:

57th Regiment,

93rd Battalion,

Armouries,

Drill Hall,

Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment,

History,

Murrary Street,

PCVS,

Peterborough,

Peterborough Collegiate and Vocational School

Tuesday, 1 May 2012

Major Bennett, Peterborough's first war casualty

|

| Credit: Major Bennett Bus, Flickr.com, VB5215 |

The white and green buses operated by Peterborough Transit

are on nearly every major arterial road in the city. The Major Bennett #12 bus

is a familiar sight on Aylmer Street and near the newly renovated Lansdowne

Place Mall. The commuters that use the Major Bennett route likely haven’t

considered the origin of the name. Major Bennett Drive was named after

Peterborough’s first casualty of the First World War, Major George Bennett.

|

| Photograph of Major G.W. Bennett, Credit: Peterborough Examiner, 1915 |

George Bennett was a prominent resident of the small city of

18,000 people. He was born in 1864 in North Monaghan Township and worked a

civil servant for the Government of Ontario. He rose to the prestigious rank of

Superintendent of the Department of Public Works overseeing provincial roads in Northern Ontario. The tall dark

haired 49 year old bachelor had served with the local Peterborough militia for

over 25 years. After many nights at the Peterborough Armouries on George

Street, Bennett received his officer’s commission with the 57th "Peterborough

Rangers" Regiment.

|

| Picture of troops in Ypres in June 1915 with bayonets. Note how the Belgian countryside still had trees - not yet mud and siege warfare. Credit: Wikipedia Commons |

When Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914, 115 soldiers

from Peterborough’s 57th Regiment rushed to volunteer for overseas

service. The eager Peterborough volunteers that were selected for service were

to be led by Peterborough’s own Major Bennett. The first batch of Peterborough

recruits were assigned to the 1 Company, 2nd Battalion (Eastern

Ontario) in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. After months of training in

Quebec, and in England, they took their place in the front line against the

Germans.

|

| Route of 2nd Battalion on 22 April 1915 Credit: The History of the 2nd Canadian Battalion (Eastern Ontario Regiment), C.E.F., 1947 |

At 7pm on 22 April 1915, the Bennett’s battalion witnessed

the first use of chlorine gas in warfare. Click here to read about the attack. Bennett and his men were stationed in reserve in rest billets

(huts) in the town of Vlameringhe, Belgium. Witnesses from the 2nd

Battalion recall watching French troops stagger past the Canadian lines in full

retreat; some soldiers “dropping into ditches in convulsions of vomiting.” By

8:30pm, the commander of 3rd Brigade, war hero and holder of the

Victoria Cross, Richard Turner was in a complete panic. He ordered immediate

assistance to help launch an attack that would get the Germans out of

Kitcheners’ Wood. It would take several hours of marching on Belgian roads,

stopping intermittently to let ambulances with wounded soldiers pass, before the

2nd Battalion arrived at the designated rendezvous point.

|

| Photograph of the remains of Kitcheners' Wood, taken in 1918. Credit: Great War Forum |

|

| Photograph of Kitcheners' Wood, June 1917. Credit: Greatwar.co.uk |

At roughly 10 pm, the first two Canadian units attempted to

retake Kitcheners’ Wood. Attacking from southerly direction, the 16th

Battalion and 10th Battalions made a 200 yard running charge over

open ground, facing fire from the chattering German machine guns as they

entered into the woods. Within minutes the attack had stalled, the commander of

the 10th Battalion lay bleeding to death after receiving 5 bullets to the groin. His men were now engaged in hand-to-hand fighting with Germans in

the east, west and in the interior of the wooded area. By the time roll call

came next morning, the 16th Battalion only had 193 men out of 813.

The 10th Battalion’s casualties were much worse, in a report made

three days after the battle; an officer wrote that the unit only has “a small

party of men” left.

|

| Location of Kitcheners' Wood and Canadian Monument. Credit: Google Maps |

As Major Bennett and his men felt their way forward in the

dark, they could see and hear the muzzle flashes and sound of gun fire on their

left flank. They knew that their comrades in No. 3 Company needed assistance.

After reaching cover of a hill, Bennett ordered a scout to report on the

developing situation. After examining the terrain and referencing his position

on a map, Major Bennett crawled back to his men. The battalion’s commander, Lt.

Col. Watson, approached Bennett’s lagging troops. Watson bellowed to his subordinate that an attack

must be carried out before morning. Major Bennett lay on his stomach on the

side of a hill with his men awaiting orders, he may have thought of the irony

of being in a farm field similar to his own, only thousands of miles away from North

Monaghan. Bennett was told to attack, and as a good soldier he would follow

that order.

As dawn began to break the night sky over Langemarck, Major Bennett prepared to meet his destiny. Bennett put his whistle to his lips, grabbed his service revolver out of the holster, and ordered his men to fix bayonets. After the 15 inch steel blades snapped onto the rifles, the Major stood up and ordered the men to get up. He inhaled. Waving his arm forward he blew his whistle and charged over the hill.

As dawn began to break the night sky over Langemarck, Major Bennett prepared to meet his destiny. Bennett put his whistle to his lips, grabbed his service revolver out of the holster, and ordered his men to fix bayonets. After the 15 inch steel blades snapped onto the rifles, the Major stood up and ordered the men to get up. He inhaled. Waving his arm forward he blew his whistle and charged over the hill.

The German troops in Kitcheners’ Wood saw the soldiers from

Peterborough as they descended down the sloping hill. Within seconds, the

Germans unleashed a storm of bullets against the Canadians as they ran directly

at the German line. As a leader of infantry charge, Major Bennett was one of

the first men to be hit. Survivors of the failed attack on Kitcheners’ Wood

wrote back to family in Peterborough that Major Bennett was killed instantly

when he was hit in the head and stomach with a burst of machine gun fire. Private

James Bills of Sherbrooke Street, who was wounded in the charge, wrote back home:

“The Canadians did grandly the past few weeks, but our company lost every

officer in one day. . . He [Bennett] was loved by all men in the company, and,

believe me, they would follow him anywhere.”

The 2nd Battalion attack on Kitcheners’ Wood

failed. Almost all of the soldiers No. 1 Company were killed or wounded in the

charge. After two days of fighting, the

battalion had 494 soldiers at roll call; 540 of the 1,034 men in the unit had

died, been wounded or captured. On April 25th 1914, the first news

of the battle arrived in Peterborough. Initially, the news reported that the

Canadians had succeeded; eventually word came to prepare for large numbers of causalities.

On April 28th came the news of Bennett’s death. Letters of condolence

poured in from the premier, Prime Minister, and city councillors. In early May

a large Anglican memorial service was held in Bennett’s honour. The service included

a solemn prayer for all the families in Peterborough that were in mourning or

waiting to hear information of their relatives in Ypres. His death represented

the war coming to Peterborough. For residents of the city, the Great War

was no longer a European side show that they read about in the paper.

Labels:

10th Battalion,

16th Battalion,

1st Canadian Division,

2nd Battalion,

2nd Battle of Ypres,

57th Regiment,

Kitcheners' Wood,

Major Bennett,

Peterborough,

Peterborough Transit,

Second Battle of Ypres,

Ypres

Sunday, 22 April 2012

First Gas Attack, 22 April 1915, Second Battle of Ypres

|

| Credit: Canadian War Museum, Second Battle of Ypres, 22nd April to May 1915 by Richard Jack |

|

| Credit: Library and Archives Canada, Soldier with Gas Mask, 1917 |

|

| Credit: Library and Archives Canada, 92nd Battalion, Gas Mask Drill, 15 August 1916 |

|

| Troop Dispositions, 22 April 1915. Credit: Shoestring Soldiers |

|

| Gas Cloud, 22 April 1915. Credit: Shoestring Soldiers |

“A steady tide of humanity – the most mixed and miserable lot of people I had ever seen moved by us in the direction of Ypres, leaving us barely room to squeeze through in the direction of the enemy . . . and of course there were the wounded – hundreds of them – and the main body of French colonial troops in retreat, some of whom had been gassed with yellow faces and gasping for breath.”

|

| Painting Second Battle of Ypres. Credit: Canadian War Museum |

|

| Photo of the location of 13th Battalion's trenches, now occupied by cattle. Credit: Matt Ferguson, 2009 |

It would take two days before Canadians at home heard of the German attack. The initial press reports warned Canadians “to expect many casualties.” In the following weeks, cities and towns across Canada would receive the casualty list of 5,592 of the Canadians that died, went missing, captured or were wounded in the defence of Ypres. Canada would never be the same after Ypres. It was the first time that Canada had collectively lost so many sons. Never before was there so much collective grief and mourning.

In my next entry, I will look at Peterborough’s involvement at Second Ypres.

Click Here to Read the Article

Labels:

13th Battalion,

22 April 1915,

2nd Battalion,

2nd Battle of Ypres,

Gas,

Gas Attack,

Kitcheners' Wood,

Peterborough,

WWI,

Ypres

Saturday, 21 April 2012

July 1914: the Summer Before the Storm

For anyone interested in modern European history or the

First World War, July 25th represents the collapse of the house of cards that

was European diplomacy in 1914. Germany’s first Chancellor, Otto von Bismark once

remarked, “If there is ever another war in Europe, it will come out of some

damned silly thing in the Balkans.” He couldn’t have been more correct. Before proceeding, here is brief re-cap of the events leading up to 25th of

July: the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand

is assassinated in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Austria-Hungary retaliates by demanding

the extradition of the leaders of the Black Hand (organizers of the assassination),

Serbia turns up the ante by requesting assistance from the Russian empire, and

finally, Austria’s delivers an ultimatum to Serbia. Austria had given Serbia very few options, either humiliation or fight.

Modris Eksteins’ classic book, The Rites of Spring, paints an excellent picture how July 1914 was an

abnormal summer. Conventionally, European politicians put international and

domestic issues on hold. Typically men

in suits fled the soot ridden capital cities of Paris, London and Berlin for coastal

towns like Blackpool or Marseilles. Yet the summer of 1914 was different. The

Kaiser cut short his annual yacht cruise of the Rhine. British politicians in bowler hats stayed in the London. Ordinary Germans also avoided

the seaside, preferring to await military mobilization orders.

|

| Credit: Peterborough Examiner, 1914 |

But what was life like in Peterborough during these anxious days

of July 1914? What were the average resident’s thoughts on the crisis of

European alliances? If newspapers are a reflection of popular public opinion,

then we can safely assume that war was not on the minds of locals. After

looking at the 25 July 1914 edition of the Examiner, it becomes evident that picnics, church sermons, local camping excursions to Stoney lake with school children

from Pennsylvania were more pressing issues. Internationally, Peterborough was more concerned with the crisis of Irish rebellion and Home Rule than

some “damned silly thing in the Balkans.” A big local stories for press included the report of the removal of a gang of local Gypsies and dodgy fortune tellers from the city's streets. Only at the bottom of the front page was there any mention of how Europe stood on the brink of war caused by Austria’s ultimatum to tiny Serbia.

It is almost bittersweet to look back at this pre-war

period. They didn't see it coming. It is the end of the Edwardian period and the birth of the modern age.

In 2 weeks’ time, the Dominion of Canada would be at war, and the local

Armouries would send off hundreds of men overseas, many of the enlisted

recruits would never return, and many of those who did come back, did not come

back mentally whole.

The British Statesman Sir Edward Grey, said it best when overlooking London after it had been resolved that Britain would declare

war on Germany. As he watched the last night that the gas lights were being lit in peacetime, he wrote: “The

lights are going out all over Europe: we shall not see them lit again in our

lifetime."

Labels:

Berlin,

Edward Grey,

Franz Ferdinand,

Home Rule,

July 1914,

Modris Eksteins,

Otto Von Bismark,

Paris,

Peterborough,

Pre-War,

WWI

Thursday, 19 April 2012

Another Peterboro' Boy Lays Down his Life at the Front

Another Peterboro' Boy Lays Down his Life at the Front

|

| Credit: Peterborough Examiner, 2 May 1916 |

Another Peterborough boy has given his life for the Empire

in the great struggle in Europe. This morning J.W. Edwards, 485 Sherbrooke

Street, received the sad news that her son, Corp. Herbert Simon Wesley

Edwards, 4th Canadian

Infantry Brigade is officially reported to have died of wounds at No. 10

Casualty Clearing Station on April 26th.

Corp. Edwards is a native son of Peterborough, having been

born in this city in September 1895. His Father, Pioneer Sgt. J. Wes

Edwards, who is at West Sandling Camp, England with the 39th

Battalion, is one of the best known Peterborough men who has gone overseas.

Having been a member of 57th Regiment for over 25 years. His son,

Corporal Edwards, now reported died of wounds enlisted here in January 1915

with the 39th Battalion, after having tried in vain to go with the

first contingent. He became a member of the of the Machine Gun section of the

39th and after training in England, was drafted into a 4th

Brigade Infantry Battalion and went to the front. His letters home have been

bright, cheery nature, showing that he was taking the hardships at the front

philosophically as a soldier should. In a recent letter to his father in

England, he had expressed hope that they might be able to arrange to Mrs.

Edwards come over England to visit her husband and son.

Corp. Edwards last visit home in Peterborough of Pte.

Nicholls funeral of the 39th Battalion who died at Belleville Camp.

Edwards was a member of the firing party on that occasion.

In addition to his sorrowing parents he is survived by a

younger brother, Reginald and two younger sisters, Mrs. Elliot wife of Lance

Corp. Elliot of 93rd Battalion, and Mrs. C. E. Hemalt of Toronto.

The young soldier was a bright likable boy and was very

popular in the city and among members of the 39th Battalion.

-- Grave Inscription: Corp. H.S.W. Edwards, Age 21, Canadian Machine Gun Corps. "He gave his life for us so that we might live." [Ed. - It is interesting to note that his mother, Lizzie, is listed as living 182 Strachan Ave, Toronto.]

Labels:

39th Battalion,

4th infantry Brigade,

57th Regiment,

93rd Battalion,

Canadian Machine Gun Corps,

Corp. Herbert Edwards,

No. 10 Casualty Clearing Station,

Peterborough,

Pte. Nicholls,

West Sandling Camp

Peterborough in 1914

|

| Times (London, UK) Newspaper Headline - 5 August 1914 |

With that spirit in mind, I am going to attempt to show what life was like in Peterborough in 1914 before the outbreak of war.

1. Price of an automobile in 1914 was roughly $550 -$ 1050. Some automobiles cost as much as $4,000 Average Canadian wage for a worker in 1914? $417.

2. Transportation: Many residents in Peterborough got around town in streetcars (yes, we had tracks down main thoroughfares), train or bicycle. Some die-hard citizens still used horses to get around, mostly in the country side. There was also a daily horse drawn buggies that would commute back and forth from Ennismore to Peterborough, and Havelock every day.

3. The city of Peterborough only had the population of 18,360. Today, our population is

78,000.

4. Peterborough was known as the Electric City, thanks in part due to the large General Electric factory that employed roughly 2000 people. The pride of Peterborough, our Lift lock was only 10 years old in 1914.

5. Women in Peterborough could not vote. Women fought for suffrage and liquor/alcohol prohibition in the years leading up to the Great War. The Prohibition movement had taken a foothold in the Peterborough area; many Women’s Institutes advertised meetings on prohibition in the local papers in 1914.

6. Our Prime Minister was the dapper mustached Conservative Robert Borden. Peterborough was a Blue Tory city. Both ridings of Peterborough East and West elected Conservatives in the 1911 federal election. The results were not surprising, given Peterborough’s close proximity to the town of Lindsay, Ontario, home of the popular fire-brand Orange Order conservative and Minister of Militia Sam Hughes.

7. Peterborough was in the throes of a deep economic recession from 1913. The Peterborough examiner of 1914 attests to the unemployment problem, with many reports of ‘vagrants’ and ‘delinquents’ on the court docket. One advertisement in an April 1914 edition of the Examiner mentions that the Salvation Army was looking for donations for the 4,000 families in Peterborough that were in need of 'relief'

8. Workman’s Compensation Act was enacted in 1914. Workplace injury was very common in 1914. The Peterborough Examiner is filled with reports of workers losing limbs in factory machines, and reports of men falling to death at the Quaker Oats Factory at the grain elevator.

9. Divorce – was next to impossible in 1914 to get a divorce in Peterborough. Couples needed to petition to Parliament for a statutory divorce. The most couples that sought separation prior to WWI simply deserted their spouse or filed for legal separation. There was no such thing as Child support.

10. Residents did not pay income tax in Peterborough in 1914. The “temporary” income tax was introduced in 1917 by Finance minister Thomas White.

11. School children in Peterborough would sing Rule Britannia, God Save the King, and Maple Leaf Forever in schools. Children of Peterborough were often reminded that they were a part of the world’s largest empire, ruled by King George V in 1914. Popular children's books in 1914 included the Boy's Own series, Chums, and books by the author Ralph Connor. Novels by Ralph Connor sold like hot cakes in Canada, which often exposed young Canadian boys to the ideal of a 'masculine Christianity.'

12. Infrastructure in Peterborough: many areas of Peterborough still had dirt roads in 1914 (and you think driving on the washboard on Charlotte Street now is bad…) and city council was still debating the cost and merit of installing electricity to all areas of the city in 1914. Prior to the Great War, only major roads in downtown Peterborough were paved. Maps and Pictures from 1913 show only the roads from Aylmer to Hunter as paved. Charlotte Street was only paved in 1915.

13. Mass communication in Peterborough: Want to send e-mail in 1914? Forget it. The closest thing to instant communication was the telegram. Want to call a friend in 1914? Pick up the phone and dial three numbers to connect to the operator. Don’t forget to tell the operator which residence you wished to be connected with. According to records, only a 1000 people in Peterborough had phones in 1914.

14. Movies and Music: Forget Ipods, Itunes, and Radios. Peterborough had 3 record stores in 1914. If you want to hear the newest version of It’s a Long Way to Tipperary before buying it, you had to go into the store and sit in the booth to hear the song. Remember, radio was still in it infancy in 1914, radio stations only began to receive licences in 1919. Wanted to go to the movies in 1914? Peterborough had 2 moving picture shows in 1914. In June 1916 the Peterborough Examiner advertised two films: a Charlie Chaplin film called the Floorwalker, or the British propaganda film entitled Britain Prepared. Remember, they were silent films.

15. Canada in 1914: In 1914, we had roughly 7.8 million people. If you walked in almost any street in Canada in 1914, you would have heard a foreign accent. In the period between 1900 - 1914, 2.9 million immigrants came to Canada. That means that 37.75% of Canada's population had arrived in Canada in the previous 14 years leading up to the Great War. Amazing.

16. Immigration: Canada had accepted 2.9 million new immigrants to Canada in the period between 1900 - 1914, but that is not to say that we were a tolerant society in 1914. Immigrants of British/Anglo-Saxon heritage were preferred. Immigrants from Asia were almost excluded to Canada with the enactment of the Chinese Head Tax in 1903 (it cost roughly $500 to come to Canada, an astronomical sum for Asian immigrants). In the summer of 1914, as Europe stood on the brink of war, the politicians in British Columbia were busy with the Komagata Maru affair. In 1914, a ship from India carrying mostly Sikh immigrants tried to dock in Vancouver, after a heated standoff, the ship of 376 potential Indian immigrants were sent back to India.

15. Canada in 1914: In 1914, we had roughly 7.8 million people. If you walked in almost any street in Canada in 1914, you would have heard a foreign accent. In the period between 1900 - 1914, 2.9 million immigrants came to Canada. That means that 37.75% of Canada's population had arrived in Canada in the previous 14 years leading up to the Great War. Amazing.

16. Immigration: Canada had accepted 2.9 million new immigrants to Canada in the period between 1900 - 1914, but that is not to say that we were a tolerant society in 1914. Immigrants of British/Anglo-Saxon heritage were preferred. Immigrants from Asia were almost excluded to Canada with the enactment of the Chinese Head Tax in 1903 (it cost roughly $500 to come to Canada, an astronomical sum for Asian immigrants). In the summer of 1914, as Europe stood on the brink of war, the politicians in British Columbia were busy with the Komagata Maru affair. In 1914, a ship from India carrying mostly Sikh immigrants tried to dock in Vancouver, after a heated standoff, the ship of 376 potential Indian immigrants were sent back to India.

Labels:

Borden,

Havelock,

Immigration,

Peterborough,

Prohibition,

Recession,

Sir Sam Hughes,

Suffrage,

Transportation

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)