The genesis of the second Battle of Fresnoy began on 5 May

1917. Orders were received by the 5th Bavarian Division to prepare for

a counterattack (Gegenangriff zum Fresnoy). Fresnoy and surrounding wooded area was an integral

piece of the Oppy-Mericourt defence line. After the successful capture of the

village, the British and Canadians were in possession of a minor salient

that had the potential to breech the fortress that was the Hindenburg Line. The

German High Command knew that in a worst case scenario, if the defence network was overcame, then the allies

would have a opportunity to change the nature of the conflict from trenches to a war of rapid mobile warfare. Fresnoy had to be recaptured.

|

| German Prisoners captured by Canadians in the Arras Sector, May 1917 Credit: Veterans Affairs Canada |

The two prior attempts to re-take Fresnoy on May 3rd were repulsed with artillery and defensive fire; the attacks were

hastily planned and were aimed to simply overwhelm the battle fatigued Canadians. The

renewed attack by the 5th Bavarian Division was planned to be a more

organized push, involving a heavy reliance on artillery and additional soldiers. The

Germans planned to launch their assault only after weakening the lines with

artillery, identifying defence strongpoints, and isolating routes where re-enforcements could be brought into the battle. Starting on May 6th the Germans began to shell the vicinity around the objective. In a span of two days, German artillery fired over 100,000 shells into British and

Canadian sector.

|

| German Photograph of the Arras Sector. Credit: GreatWarPhotos.com, Paul Reed |

To the north of the German objective was the 6th Canadian

Infantry Brigade. They were stationed north of Fresnoy Wood and were scheduled

to be relieved by the 4th Brigade on the night of May 7/8.

The British 95th Brigade, 12th Battalion Gloucester

Regiment occupied the shelled out remains of the town of Fresnoy. The British had constructed gun pits, dugouts, and 2 lines of trenches. The

landscape of the village had changed drastically in the previous month. The

town had been shelled on a consistent basis since mid-April. Famous German

author Ernst Junger was stationed in Fresnoy before it was turned into a rubble

heap. Junger wrote: “As I entered the village at the end of one of these ordeals

by fire - as that's what they were - I saw a basement flattened. All we could

recover from the scorched space were the three bodies. Next to the entrance one

man lay on his belly in a shredded uniform.” From the 6th of May to the 8th it was the Tommy's turn cower in the ruins of village.

On the rainy evening of 7 May reports were received and 2nd

Canadian Division’s HQ at 7:20 pm that the German bombardment had intensified,

with heavy calibre shells hitting positions between Acheville in the north and

Oppy in the south. Around the same time, the German artillery began firing gas

shells at suspected targets where Anglo-Canadian artillery guns were located. Gun

crews were forced to wear gas masks to minimize the effects of the chlorine gas. The masks saved the lungs of the artillerymen, but it greatly

reduced efficiency and ability to rapidly fire the guns.

|

| Map of Canadian Corps Operations, Fresnoy located on right. Credit: WFA |

As the Canadian units were finishing their rotation to the front,

all hell broke loose. At 3:45 am, the German attack began. German artillery

launched a terrific final bombardment on the town, and then began gassing all nearby road junctions. The rain and mist that night made for

very limited visibility for the British defenders. The German commanders picked the most

opportune time to attack. They had launched their counter-attack when the weather

favoured an assault with poor visibility. Many of the Canadian defenders that

were at the front were unfamiliar with

their new trenches. The Canucks were unacquainted with this new section of the line. To make

matters worse, roughly 1/3 of all the Canadians that were in the trenches that

night were fresh faced re-enforcements. They had just come over to France in the days after the

Battle of Vimy Ridge, and now these green soldiers would face their first fight.

The Bavarian 7th, 19th, and 21st Regiments launched

their attack primarily on the British lines and were able to infiltrate the

British trenches on the north east section of the line. As the Germans

approached the British lines, the rain soaked Lewis Gunner Sgt. Henry Civil went into action. He saw enemy running towards his line in mass formation and he opened fire. Sgt. Civil recalls hitting plenty of Germans that dark early morning, but his efforts

could not stem the tide of the attack. The Germans poured down the trenches tossing grenades

and firing upon opposition that they encountered. Civil soon realized

he was alone, he had held up a platoons of enemy, but he was running low on ammunition and his gun had been damaged beyond repair. He withdrew to the sunken road,

which lay to the west of the village (near Arleux).

|

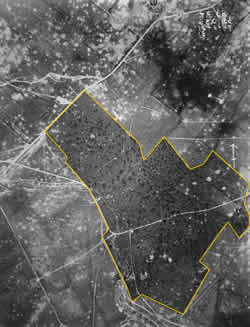

| Map of the German Attack. 8 May 1917 Credit: Google Earth |

|

| Germans Marching British Prisoners.Survivors of Fresnoy may be in marching in this group. Credit: GreatWarPhotos.com, Paul Reed |

By mid-day it was obvious that Fresnoy was lost. The 12th

Battalion Gloucester Regiment lost 288 men, and the 19th Battalion (Central Ontario) lost 236 men, plus another 16 were taken as POWs. In the aftermath of the battle, several

theories were put forth as explanations for the loss of ground. In the 12th

Gloucs Official Records, they list several factors such as: “Lack of artillery

support of any kind, Lack of aeroplanes, bad weather. . . visibility being

NIL, Attempting to hold an impossible salient as a defensive position.” In the

Canadian Official History of First World War, the blame falls squarely in the

lap of the British artillery. The British narrative

assigns guilt to the poor quality of British re-enforcements, noting that the

Canadians had men in better physical condition.

Ultimately, the blame for the poor defence should be

attached to the commanders, from brigade up to the divisional level. The 2nd

Division commander, Gen. Burstall, made the mistake of not launching an

immediate counter attack. The wet and muddy conditions on May 8th

were advantageous for a counter attack. In a post-battle report, the 5th

Bavarian Division noted that almost all machine guns were inoperable due to

mud clogging the barrels. Even greater than the mistake of not launching a rapid counter attack, was the pre-battle deployment of nearby units and poor coordination between neighbouring artillery batteries. The 2nd Division held several brigades and batteries behind the relative safety of Farbus Wood. Once the German attack on Fresnoy

began, they shelled all routes leading to Fresnoy, cutting off the potential for any substantial reinforcement and counter battery fire. Without reinforcement, the under strength 19th Battalion (at the time of attack it had 687 men - at full strength it was supposed to have roughly 1,000 men) was forced to try and save Fresnoy, which was an near impossible task.

Links:

Sgt. Civil's story - 12th Gloucs Regiment - May 8 1917

Click here to read of Canadian attack on Fresnoy of 3 May 1917.

Click here to read of Canadian attack on Fresnoy of 3 May 1917.