|

Tyne Cot Commonwealth Cemetery

Credit: Royal British Legion |

The expression “old men declare war, but the youth who

must fight and die,” comes to mind when visiting any Commonwealth War Graves

Commission Cemetery. Rows of white tombstones

mark the last resting place for a generation of young men of the British

Empire. Studies of death records have found that the majority of soldiers died

in their 20s, with the median age being 22-26 years old. Most of the soldiers were

cut down in the prime of their lives, leaving young wives and children to cope

with the loss of a missing partner and father.

Researchers have come across the graves of soldiers from the

Great War that were too young to marry, or even shave. Recently

I have come across the story of Peterborough’s youngest fatality of the Great

War, Anthony ‘Tony’ Skarrizi who died during the last days of the Battle of

Passchendaele. Private Anthony Skarrizi was 16 years and 11 months old when he

died on 3 November 1917 outside of Passchendaele, Belgium.

|

Peterborough Examiner,

22 November 1917 |

Government Records show that Anthony Skarrizi was born in

Italy in November 1900. Like many Italian immigrants at the turn of the last

century, the Skarrizi’s moved to Canada in 1907 hoping of finding employment as

labourers. The young Anthony Skarrizi decided to join the military in August 1915.

Private Skarrizi falsely attested his birth year as 1897, making the adolescent

appear to be 18 to the Recruiting Sargent at the Peterborough Armouries, in all likelihood he was only 14 years and 8 months old.

|

| Canadian Military Police Corps (Provost) |

Private Skarrizi completed his military training in Canada,

and embarked for overseas service. After sailing to Liverpool, England he was

found to be underage and redeployed for permanent base duty. Military law

states all soldiers must be 18 to enlist in the military and 19 years old for

overseas service. Once his age was discovered, Skarrizi spent 6 months on base

duty being assigned to several guard and provisional units; he became an unruly

and irresponsible soldier. His young age combined long rotations in the much

hated “bullrings” (reinforcement camps) likely contributed to his declining

morale. By the winter of 1916-1917,

Private Skarrizi had several run-ins with the Canadian Provost Corps.

|

Great War Military Depiction of

Field Punishment No 1 |

He was arrested and court martialed four times for:

neglecting to obey an NCO, absent without leave on two occasions, and absent

from parade. The young soldier was punished by being restrained, having his pay

docked, and after his second conviction for being absent without leave, he was

given the dreaded Field Post No 1. According to the Manual of military law, the

Field Post No 1 punishment consists of restraining an individual at the feet and

hands and attaching the convicted soldier to a wagonwheel, or fencepost in a

public area, whereby all other soldiers could witness the punishment.

Two months after the last conviction, Skarrizi was

transferred to France with the 21st Battalion. One month after

landing in Boulogne, France, the young private was attached to Kingston’s 21st

(Eastern Ontario) Battalion billets in Villers Au Bois. The question arises: why and how would a

known underage soldier allowed to be sent overseas? No one knows. It is likely

that Officers decided to send Skarrizi to France because serving at the front would stop the adolescent Italian-Canadian

soldier from running away from the Canadian military camps.

|

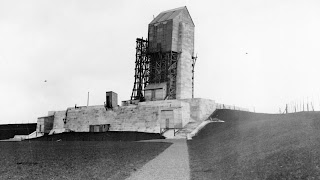

Picture of Passchendaele

Credit: Archives of Ontario/RCL |

|

Terrain of Passchendaele

Credit: Library and Archives Canada |

Unfortunately for Private Skarrizi, he joined the 21st

Battalion only several weeks before the Canadian Corps moved into Belgium to

take part in the Battle of Passchendaele. The four month long British led Passchendaele

offensive had almost ground to a halt. The British High Command jointly

employed their “shock troops” of Australian and Canadians to help

resolve the political and military mess that the British Generals had created

in attempting to take Passchendaele. The Canadian Commander, Arthur Currie, planned

to win the battle but slowly and in several phases in order to insure that the

Canadians did not suffer needless losses of men. This article will not go into the general history of the Passchendaele campaign. It is interesting to note that during the research for this entry, I found there was a lack of contemporary historical analysis into the Canadian involvement at Passchendaele.

|

Aerial Photograph of Passchendaele,

displaying location of Crest Farm |

On 30

October 1917, the first phase of the

Canadian assault at Passchendaele ended. The Canadians launched the second

phase of their attack on Passchendaele after the PPCLI and the 72

nd

Battalion provided miraculous results for the Canadian Corps. The 3

rd

Division captured two German strongholds, Meetcheele crossroads, which was

lined with concrete bunkers and Crest Farm, a swampy redoubt of trenches and

shell holes that overlooked the advances to the town of Passchendaele.

On the night of 3 November 1917 the 4th Canadian

Brigade relieved the Canadians that captured the lunar swampy landscape that

was Crest Farm at 2:45 AM. The relatively fresh 21st Battalion was

sent in to guard the recently captured Crest Farm by the 4th

Division. On the right was the 19th Battalion, and on the left the

21st Battalion was on left of Crest farm.

|

1917 Map and Location of Crest Farm

Credit: McMaster Archives |

|

Contemporary Photo of location

of Crest Farm Credit: Google Maps |

At 3:45 AM, the German started to bombard Crest Farm and

reserve and support areas. At 4:50 AM, Brigade HQ witnessed the 21

st

Battalion sending off red S.O.S. flares.

The attack by German Stoßtruppen (Storm Troops - Specialist Assault Troops) breached the

Canadian wire charged right into the 21

st and 19

th Battalions. The 19

th Battalion made quick work of the German

attackers, while on the left; the 21

st Battalion had to call in a reserve

company to help dislodge the enemy. By 6:45 AM, the Germans had launched two small

isolated attacks on the 21

st Battalion, both of which were halted. Canadian

After-Battle reports state German infantry laid in shell holes in front of the

Canadian position but were unable to advance. During the defence of Crest Farm,

the 19

th Battalion provided valuable assistance to not only the 21

st

Battalion, which suffered 203 causalities, but also to the Australians on the

right flank. The 19

th

Battalion sent almost a company sized force to help shore up the Australian

defences.

|

| Menin Gate, Leper Belgium |

During the defence of Crest Farm, 16 year old Private

Anthony Skarrizi went missing. There is no record in existence that tells

historians what happened to the young inexperienced soldier. All we know is

that he never answered his company roll call again. His name is engraved at the

monument to the missing at the Menin Gate at Leper (Ypres), Belgium. Like most

of the missing of the Great War, Private Skarrizi was likely killed by a direct

hit by an enemy shell. The impact of the explosion, and the confusion that

followed the battle hampered efforts by stretcher bearers to retrieve the body

of Private Skarrizi. After the battle, Anthony Skarrizi’s family at 656 Reid Street,

Peterborough, would receive several telegraphs and letters informing them that

their son was missing, and eventually declared dead.

__________________________________________

Author would like to acknowledge the assistance and great research work provided by the 21st Battalion Website. Please visit them at

http://www.21stbattalion.ca

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)