As the centenary for the First

World War approaches, first-person accounts have started to

populate the shelves of book stores. Anne

Nason’s grandfather, Edward W. Hermon, left a collection of hundreds of letters

that were sent to his wife, Ethel, before his untimely death during the Second

Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917. This book gives historians and the casual reader

a glimpse into the life of a Yeomanry cavalry officer in France and Belgium:

from mobilization, training, and the inner squabbling between

commissioned officers.

Edward H. Hermon’s life does not

reflect the typical life experience of many ‘Tommys’ of the Western Front. Hermon was educated at Eton, served in South

Africa with the 7th Hussars, and by all

accounts was independently wealthy gentleman. His wife and four children, affectionately nicknamed

‘chugs,’ lived in a country estate that included servants. The family engaged

in many idyllic activities such as sailing, leisurely drives, and

horseback riding. After serving in South Africa Hermon transferred his commission to the Territorial Army to avoid further deployments to India or the Near East. As a reserve cavalry officer, Hermon was mobilized

in July 1914 and landed in France with his personal batman (servant) and horses from the family estate in the spring of 1915.

The correspondence between Hermon

and his wife in 1914 - 1915 reflects the personal impact that separation due to

war can have on a couple. The reader quickly builds a great deal of sympathy. A husband at the front and a pregnant wife at home looking after four young children. Hermon’s correspondence quickly settles

into a pattern of asking for jams, cakes, meats, and cigarettes,

and requests for socks and jackets. Reading the repeated pleas for more comforts of

home may cause reader’s eyes to glaze over; but these letters embody life in

divisional reserve on the Western Front.

As the 2IC (Second in Command) for the King Edward

Horse Cavalry Regiment, Colonel Hermon sent home letters of that described

witnessing battles like Loos and Festubert from reserve. In a

conflict of primarily of barbed wire, machine gun emplacements, and trenches; horses became less relevant as weapons of war. King Edward Horse Cavalry would only be ordered into the battle once the enemy line was breached. Hermon

spent much of his time complaining to his wife about being sidelined while the

infantry were in the thick of combat. The early letters (1915 - 1916) capture

the dire situation on the front lines. The British were struggling to meet the

changing technological demands of modern war. Hermon wrote home retelling his wife that soldiers were using lacrosse sticks to scoop and throw back German

grenades, and noting how his men were receiving homemade gas masks in

June 1915. Not to mention the Shell Shortage of 1915, when British artillery batterys were only allowed to fire 6 shells a day due

to the shortage.

As the

war progressed, Hermon tired of waiting for orders to charge on horse into battle.

His letters denote a growing hostility to many commanding officers, mainly the

regiment’s Commanding Officer, and General Haig. Luckily, Col. Hermon was

afforded the opportunity to advance in rank after organizing and commanding the

divisional Grenade School. After a failed bid to become the next regimental commander, , Hermon begged his superiors to transfer him to an infantry

battalion. The popular 37 year old officer was transferred to the 27th Battalion, replacing the

Commanding Officer, whom Hermon calls "the commercial traveller with

diamond rings."

|

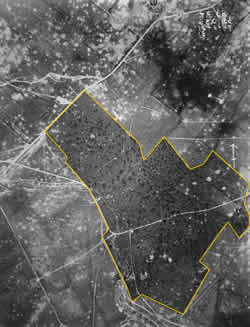

| Arras in 1919: Lt. Col. Hermon spent many weeks in Arras in 1917 Credit: Wiki Commons |

On 9 April 1917, the newly promoted Lt. Col.

Hermon took part in his first over the top assault. The 27th

Battalion along with support from tanks took their objective. Hermon and

his adjutant and was walking forward to his newly captured position when a German machine gun opened up. Eyewitness describe the German machine gun raking an abandoned British tank with fire, before taking aim at Hermon and his entourage. The enemy gun crew sprayed the officers with gun fire, and the newly promoted battalion commander was hit in the chest. Days after his death, Hermon's wife received a grief stricken letter from the batman. In the letter, Ethel Hermon was told how in her husband's last moments the mortally wounded officer told his men to 'Go On' and showed remarkable stoicism.

Ethel Hermon kept the hundreds of

letters her late husband sent to her. They were stored in a dusty dresser for years. Granddaughter and editor Anne Nason provided a valiant effort in organizing the letters, and providing

the basic background information and adding context to Hermon’s letters. There are

very few footnotes in the book, but Nason’s work provides great contribution

into the life of a mid-war cavalry officer. A highly readable book, and a valuable source of personal documents for any Military Historian interested in the BEF battles of 1915 - 1917.